|

| Claude Lévy-Strauss defines mythical

thinking as "intellectual bricolage," noting its function as a link

between artistic creation and scientific knowledge. Since his time,

interactions between artists and scientists have gained increasing

significance as rediscovered forms of cultural encounter and

knowledge transfer. Such interactions create a framework for

reflecting on the fast-paced developments in new media and

technologies. Modern society exists in a world it must "acquire."

The means people use to "acquire" the world are largely due to the

efforts of science. A world without science, research and the

resulting developments is unthinkable. Despite this, the

relationship between science and society is not simple, because

scientific developments often lead to problems which cannot be

solved by scientific means. The opportunities provided by art and

culture in this regard are seldom realized. |

|

|

|

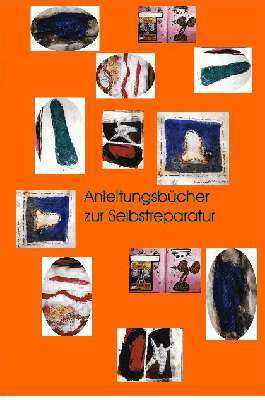

Against this backdrop, the Munich Department of

Culture has used a project of Munich artist Nele Stroebel to

introduce a key concept of our culture in all its artistic,

scientific, and social contexts: r e p a i r. This concept has been

reinfused with value through the impact of the new media and

technologies, changes in the relationship between man and machine,

and finally, through the events of the past century. Repair is a

cultural act of restoring items, bodies and souls, nature and

culture. Given the constant and increasing vulnerability of our

bodies, our cultural, economic, and military symbols, and the

stepwise destruction of nature, repair has become an inevitable

component of human life. Repair is also a creative process which

highlights aesthetic differences while transforming the "old" into

the "new."

Against this backdrop, the Munich Department of

Culture has used a project of Munich artist Nele Stroebel to

introduce a key concept of our culture in all its artistic,

scientific, and social contexts: r e p a i r. This concept has been

reinfused with value through the impact of the new media and

technologies, changes in the relationship between man and machine,

and finally, through the events of the past century. Repair is a

cultural act of restoring items, bodies and souls, nature and

culture. Given the constant and increasing vulnerability of our

bodies, our cultural, economic, and military symbols, and the

stepwise destruction of nature, repair has become an inevitable

component of human life. Repair is also a creative process which

highlights aesthetic differences while transforming the "old" into

the "new." |

|

|

|

Not everything can be repaired, however.

There are limits to repair. Some things are reparable, some

irreparable. This book seeks to show the reader a wide range of

repairs which unites many different reflections and sketches in an

interdisciplinary approach to repairing the world. In his

philosophical introduction, Bernhard Waldenfels expands on the

connection between things, bodies, and repair, in relationship to

chronological and economic factors as well as in the comparison of

old and new. Heidrun Friese points to the impossibility of

recapturing an original context, and thus to the hopelessness of

reconstructing something during the repair process. Ulrike

Leuschner views the text-critical edition of a manuscript as repair

in the context of literature, a process which reflects the constant

changes in the cultural memory. She calls the so-called "spelling

reform" in Germany a very strange type of repair, and considers

"repairs" of older works to conform to the new spelling rules to be

worthless. Hartfrid Neunzert and Marlene Lauter highlight repairs

in museums. While Neunzert supports repair that preserves an

object's actual state, documenting any changes and thus

counteracting falsification of its history, Lauter compares the

difficulties in procuring art with those of craftsmanlike

repairs. Not everything can be repaired, however.

There are limits to repair. Some things are reparable, some

irreparable. This book seeks to show the reader a wide range of

repairs which unites many different reflections and sketches in an

interdisciplinary approach to repairing the world. In his

philosophical introduction, Bernhard Waldenfels expands on the

connection between things, bodies, and repair, in relationship to

chronological and economic factors as well as in the comparison of

old and new. Heidrun Friese points to the impossibility of

recapturing an original context, and thus to the hopelessness of

reconstructing something during the repair process. Ulrike

Leuschner views the text-critical edition of a manuscript as repair

in the context of literature, a process which reflects the constant

changes in the cultural memory. She calls the so-called "spelling

reform" in Germany a very strange type of repair, and considers

"repairs" of older works to conform to the new spelling rules to be

worthless. Hartfrid Neunzert and Marlene Lauter highlight repairs

in museums. While Neunzert supports repair that preserves an

object's actual state, documenting any changes and thus

counteracting falsification of its history, Lauter compares the

difficulties in procuring art with those of craftsmanlike

repairs. |

|

|

|

A report from the practice of architect

Ingrid Krau documents repairs to anything as the result of varying

theoretical analyses. This leads her to raise questions about the

quality of expert opinions. Using the restoration of the Munich

Pinakothek as an example, Friedrich Kurrent shows the productive

union of old and new. "Especially the message found in a dense

building material with new parts is that which jumps out at us from

the building's physiognomy; it speaks of the building's history; it

doesn't conceal its destruction; it tells its entire history." This

way of handling history shows the value of memory and oblivion in

man's cultural as well as psychological processes. In a

retrospective on Alexandria, the city of his birth, Alfred Ridgeley

writes that he was only able to heal the wounds of emigration after

returning to his native Egypt. Tortured memories of his homeland

only lost their traumatic effect after Ridgeley was finally able to

confront reality. A report from the practice of architect

Ingrid Krau documents repairs to anything as the result of varying

theoretical analyses. This leads her to raise questions about the

quality of expert opinions. Using the restoration of the Munich

Pinakothek as an example, Friedrich Kurrent shows the productive

union of old and new. "Especially the message found in a dense

building material with new parts is that which jumps out at us from

the building's physiognomy; it speaks of the building's history; it

doesn't conceal its destruction; it tells its entire history." This

way of handling history shows the value of memory and oblivion in

man's cultural as well as psychological processes. In a

retrospective on Alexandria, the city of his birth, Alfred Ridgeley

writes that he was only able to heal the wounds of emigration after

returning to his native Egypt. Tortured memories of his homeland

only lost their traumatic effect after Ridgeley was finally able to

confront reality. |

|

|

|

Peider A. Defilla and Hildegard Kronawitter write

on the chances and risks of political repairs while Anneliese Durst

discusses the need for repairs in regard to unemployment. More than

ever, we need community projects which ensure the future of work in

our society, and thus, humane forms of life. The texts of this book

show that repairs are an inherent component of our cultural spaces.

They are necessary in every area, but can develop negative

momentum, as Lydia Andrea Harl shows by comparing how we deal with

the world and how we deal with the human body - both fields of

experimentation for approaching the limits of the possible.

Finally, Paul Parin exposes the strange helplessness of surgically

repairing wounds resulting from war. "How absurd it is to spend

time patching up mutilated victims of violence in a makeshift and

incomplete manner when one knows that power struggles and the

seemingly insatiable processes of industrial production constantly

create new victims, that murders occur every day, and new wounds as

well."

Peider A. Defilla and Hildegard Kronawitter write

on the chances and risks of political repairs while Anneliese Durst

discusses the need for repairs in regard to unemployment. More than

ever, we need community projects which ensure the future of work in

our society, and thus, humane forms of life. The texts of this book

show that repairs are an inherent component of our cultural spaces.

They are necessary in every area, but can develop negative

momentum, as Lydia Andrea Harl shows by comparing how we deal with

the world and how we deal with the human body - both fields of

experimentation for approaching the limits of the possible.

Finally, Paul Parin exposes the strange helplessness of surgically

repairing wounds resulting from war. "How absurd it is to spend

time patching up mutilated victims of violence in a makeshift and

incomplete manner when one knows that power struggles and the

seemingly insatiable processes of industrial production constantly

create new victims, that murders occur every day, and new wounds as

well." |

|

|

|

At the end of this book, one thing is clear: the term

"repair" has many meanings and connotations which are themselves

constantly changing. Concluding with the words of Schultes and

Schoeffel, "The concepts of being w o r t h repairing and of n e e

d i n g repair show the particularly human relativity of the idea

of repair. In the final analysis, both of these concepts - being

worth repairing as well as needing repair - are inherently

subjective." At the end of this book, one thing is clear: the term

"repair" has many meanings and connotations which are themselves

constantly changing. Concluding with the words of Schultes and

Schoeffel, "The concepts of being w o r t h repairing and of n e e

d i n g repair show the particularly human relativity of the idea

of repair. In the final analysis, both of these concepts - being

worth repairing as well as needing repair - are inherently

subjective." |

|

|

|

|

Against this backdrop, the Munich Department of

Culture has used a project of Munich artist Nele Stroebel to

introduce a key concept of our culture in all its artistic,

scientific, and social contexts: r e p a i r. This concept has been

reinfused with value through the impact of the new media and

technologies, changes in the relationship between man and machine,

and finally, through the events of the past century. Repair is a

cultural act of restoring items, bodies and souls, nature and

culture. Given the constant and increasing vulnerability of our

bodies, our cultural, economic, and military symbols, and the

stepwise destruction of nature, repair has become an inevitable

component of human life. Repair is also a creative process which

highlights aesthetic differences while transforming the "old" into

the "new."

Against this backdrop, the Munich Department of

Culture has used a project of Munich artist Nele Stroebel to

introduce a key concept of our culture in all its artistic,

scientific, and social contexts: r e p a i r. This concept has been

reinfused with value through the impact of the new media and

technologies, changes in the relationship between man and machine,

and finally, through the events of the past century. Repair is a

cultural act of restoring items, bodies and souls, nature and

culture. Given the constant and increasing vulnerability of our

bodies, our cultural, economic, and military symbols, and the

stepwise destruction of nature, repair has become an inevitable

component of human life. Repair is also a creative process which

highlights aesthetic differences while transforming the "old" into

the "new." Not everything can be repaired, however.

There are limits to repair. Some things are reparable, some

irreparable. This book seeks to show the reader a wide range of

repairs which unites many different reflections and sketches in an

interdisciplinary approach to repairing the world. In his

philosophical introduction, Bernhard Waldenfels expands on the

connection between things, bodies, and repair, in relationship to

chronological and economic factors as well as in the comparison of

old and new. Heidrun Friese points to the impossibility of

recapturing an original context, and thus to the hopelessness of

reconstructing something during the repair process. Ulrike

Leuschner views the text-critical edition of a manuscript as repair

in the context of literature, a process which reflects the constant

changes in the cultural memory. She calls the so-called "spelling

reform" in Germany a very strange type of repair, and considers

"repairs" of older works to conform to the new spelling rules to be

worthless. Hartfrid Neunzert and Marlene Lauter highlight repairs

in museums. While Neunzert supports repair that preserves an

object's actual state, documenting any changes and thus

counteracting falsification of its history, Lauter compares the

difficulties in procuring art with those of craftsmanlike

repairs.

Not everything can be repaired, however.

There are limits to repair. Some things are reparable, some

irreparable. This book seeks to show the reader a wide range of

repairs which unites many different reflections and sketches in an

interdisciplinary approach to repairing the world. In his

philosophical introduction, Bernhard Waldenfels expands on the

connection between things, bodies, and repair, in relationship to

chronological and economic factors as well as in the comparison of

old and new. Heidrun Friese points to the impossibility of

recapturing an original context, and thus to the hopelessness of

reconstructing something during the repair process. Ulrike

Leuschner views the text-critical edition of a manuscript as repair

in the context of literature, a process which reflects the constant

changes in the cultural memory. She calls the so-called "spelling

reform" in Germany a very strange type of repair, and considers

"repairs" of older works to conform to the new spelling rules to be

worthless. Hartfrid Neunzert and Marlene Lauter highlight repairs

in museums. While Neunzert supports repair that preserves an

object's actual state, documenting any changes and thus

counteracting falsification of its history, Lauter compares the

difficulties in procuring art with those of craftsmanlike

repairs. A report from the practice of architect

Ingrid Krau documents repairs to anything as the result of varying

theoretical analyses. This leads her to raise questions about the

quality of expert opinions. Using the restoration of the Munich

Pinakothek as an example, Friedrich Kurrent shows the productive

union of old and new. "Especially the message found in a dense

building material with new parts is that which jumps out at us from

the building's physiognomy; it speaks of the building's history; it

doesn't conceal its destruction; it tells its entire history." This

way of handling history shows the value of memory and oblivion in

man's cultural as well as psychological processes. In a

retrospective on Alexandria, the city of his birth, Alfred Ridgeley

writes that he was only able to heal the wounds of emigration after

returning to his native Egypt. Tortured memories of his homeland

only lost their traumatic effect after Ridgeley was finally able to

confront reality.

A report from the practice of architect

Ingrid Krau documents repairs to anything as the result of varying

theoretical analyses. This leads her to raise questions about the

quality of expert opinions. Using the restoration of the Munich

Pinakothek as an example, Friedrich Kurrent shows the productive

union of old and new. "Especially the message found in a dense

building material with new parts is that which jumps out at us from

the building's physiognomy; it speaks of the building's history; it

doesn't conceal its destruction; it tells its entire history." This

way of handling history shows the value of memory and oblivion in

man's cultural as well as psychological processes. In a

retrospective on Alexandria, the city of his birth, Alfred Ridgeley

writes that he was only able to heal the wounds of emigration after

returning to his native Egypt. Tortured memories of his homeland

only lost their traumatic effect after Ridgeley was finally able to

confront reality. Peider A. Defilla and Hildegard Kronawitter write

on the chances and risks of political repairs while Anneliese Durst

discusses the need for repairs in regard to unemployment. More than

ever, we need community projects which ensure the future of work in

our society, and thus, humane forms of life. The texts of this book

show that repairs are an inherent component of our cultural spaces.

They are necessary in every area, but can develop negative

momentum, as Lydia Andrea Harl shows by comparing how we deal with

the world and how we deal with the human body - both fields of

experimentation for approaching the limits of the possible.

Finally, Paul Parin exposes the strange helplessness of surgically

repairing wounds resulting from war. "How absurd it is to spend

time patching up mutilated victims of violence in a makeshift and

incomplete manner when one knows that power struggles and the

seemingly insatiable processes of industrial production constantly

create new victims, that murders occur every day, and new wounds as

well."

Peider A. Defilla and Hildegard Kronawitter write

on the chances and risks of political repairs while Anneliese Durst

discusses the need for repairs in regard to unemployment. More than

ever, we need community projects which ensure the future of work in

our society, and thus, humane forms of life. The texts of this book

show that repairs are an inherent component of our cultural spaces.

They are necessary in every area, but can develop negative

momentum, as Lydia Andrea Harl shows by comparing how we deal with

the world and how we deal with the human body - both fields of

experimentation for approaching the limits of the possible.

Finally, Paul Parin exposes the strange helplessness of surgically

repairing wounds resulting from war. "How absurd it is to spend

time patching up mutilated victims of violence in a makeshift and

incomplete manner when one knows that power struggles and the

seemingly insatiable processes of industrial production constantly

create new victims, that murders occur every day, and new wounds as

well." At the end of this book, one thing is clear: the term

"repair" has many meanings and connotations which are themselves

constantly changing. Concluding with the words of Schultes and

Schoeffel, "The concepts of being w o r t h repairing and of n e e

d i n g repair show the particularly human relativity of the idea

of repair. In the final analysis, both of these concepts - being

worth repairing as well as needing repair - are inherently

subjective."

At the end of this book, one thing is clear: the term

"repair" has many meanings and connotations which are themselves

constantly changing. Concluding with the words of Schultes and

Schoeffel, "The concepts of being w o r t h repairing and of n e e

d i n g repair show the particularly human relativity of the idea

of repair. In the final analysis, both of these concepts - being

worth repairing as well as needing repair - are inherently

subjective."